LA JOLLA, CA—Cells in the gut send secret messages to the immune system. Thanks to new research from La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI) scientists, we can finally get a look at what they’re saying.

A new study in Science Immunology reveals how the barrier cells that line the intestines send messages to the patrolling T cells that reside there. These cells communicate by expressing a protein called HVEM, which prompts T cells to survive longer and move more to stop potential infections.

“The research shows how barrier cells in the intestine, structural elements of the tissue, and resident immune cells communicate to provide host defense,” says LJI Professor and Chief Scientific Officer Mitchell Kronenberg, Ph.D., senior author of the new study.

Barrier cells, or “epithelial” cells, form a one-cell thick layer that lines the gut. One can picture these cells lining up like a busy queue outside a nightclub. The epithelial cells squish together. They jostle each other and chat. Meanwhile, T cell security guards circulate around the line, looking up and down the block for signs of trouble. “These T cells move around the epithelial cells as if they are truly patrolling,” says Kronenberg.

But what keeps these T cells in the epithelium to do their job?

“We’ve got some insight on what gets T cells to the gut, but we need to understand what keeps them there,” says Kronenberg. In fact, a lot of immune cells reside long-term in specific tissues. By understanding the signals that keep T cells in certain tissues, Kronenberg hopes to shed light on conditions like inflammatory bowel disease, where far too many inflammatory T cells gather in the bowel.

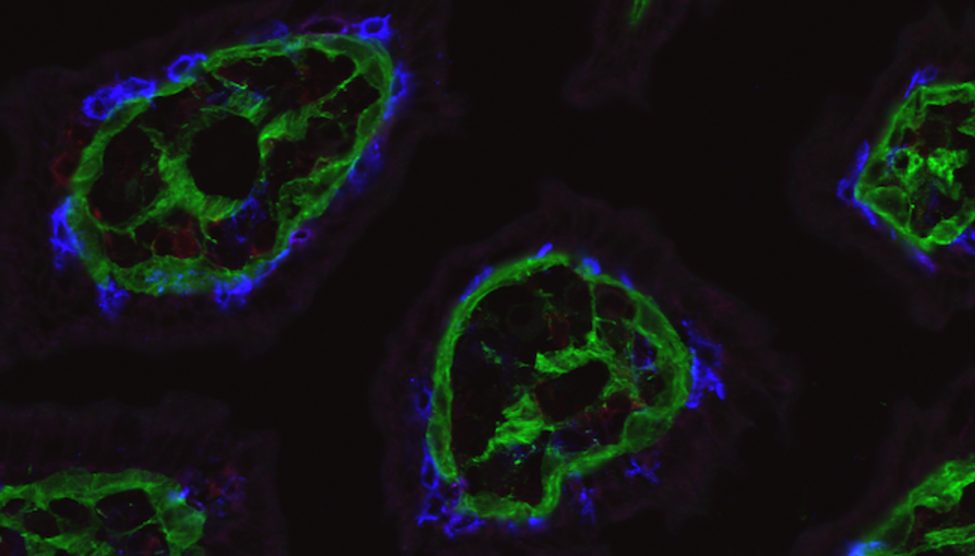

This image from the LJI Microscopy Core captures intraepithelial T cells (blue dots) and collagen in the basement membrane (green). This view shows how the cells and the basement membrane are connected. The black space is not empty–it is filled with cells in the intestinal villus, but they were not labeled with fluorescent antibodies so they do not show up.

In the new study, the researchers found that important signals in the gut are sent through the basement membrane, a thin layer of proteins beneath the epithelium. In our nightclub scene, the basement membrane would be the sidewalk where everyone stands.

Their experiments show that epithelial cells receive signals through HVEM proteins on their surface that stimulate synthesis of basement membrane proteins. The team found that without HVEM, the epithelial cells couldn’t do their job because they produced less collagen and other structural components needed to maintain a healthy basement membrane.

T cells detect the basement membrane via adhesion molecules they express on their surface, called integrins. The interaction of the T cell integrins with the basement membrane proteins promotes messages that allow the T cells to survive and patrol in the epithelium. It is as if the epithelial cells have written messages on the sidewalk: “Stay here,” “Patrol here,” “Do your job.” Without a sufficient basement membrane, T cells could not survive as well or go on patrol.

Using a mouse model, the researchers then showed that removing HVEM expression—only in the gut epithelial cells—was a major blow to gut health. Patrolling T cells could not survive as well and they didn’t move as much. These T cells made lousy security guards. When challenged with Salmonella typhimurium, an invasive bacterium that causes gastroenteritis, the T cells allowed the infection to take over the intestines and spread to the liver and spleen. Therefore, HVEM from epithelial cells laid the groundwork for T cells to guard the gut—it was the very reason they survived in the epithelium—communicating with the T cells indirectly through the basement membrane.

These insights came from a series of experiments spearheaded by study first authors Goo-Young Seo, Ph.D., Instructor at LJI, and Daisuke Takahashi, Ph.D., formerly of LJI and now at Keio University in Tokyo. The team worked closely with the LJI Microscopy Core, the LJI Flow Cytometry Core, and employed intra-vital imaging RNA sequencing techniques to investigate HVEM’s role in the gut.

Going forward, Kronenberg and his colleagues are interested in investigating the role of HVEM in maintaining a healthy population of gut microbes. Kronenberg says there are signs that a lack of HVEM can sway the composition of the gut microbiome even in the absence of pathogenic bacteria.

Additional authors of the study, “Epithelial HVEM maintains intraepithelial T cell survival and contributes to host protection,” include Qingyang Wang, Zbigniew Mikulski, Angeline Chen, Ting-Fang Chou, Paola Marcovecchio, Sara McArdle, Ashu Sethi, Jr-Wen Shui1, Masumi Takahashi, Charles D. Surh and Hilde Cheroutre.

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants P01 DK46763, R01 AI61516 and MIST U01, AI125955, MIST U01 AI125957, S10RR027366, and S10OD021831), the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America (grant CCFA-254582), a Uehrara Foundation grant, and a Chan- Zuckerberg Initiative Imaging Scientist Grant.

DOI: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abm6931

###