The immune system wants to attack pathogens and cancers—not a person’s own tissues. To do this, the immune system needs to communicate with all the other cells in the body.

Healthy beta cells in the pancreas can talk to the immune system by displaying special markers—little molecular flags—to tell other cells “I’m supposed to be here!” Some of these markers are HLA molecules. Along with other proteins, HLA molecules can influence the immune response, for instance, by stopping immune cells from attacking the body’s own tissues.

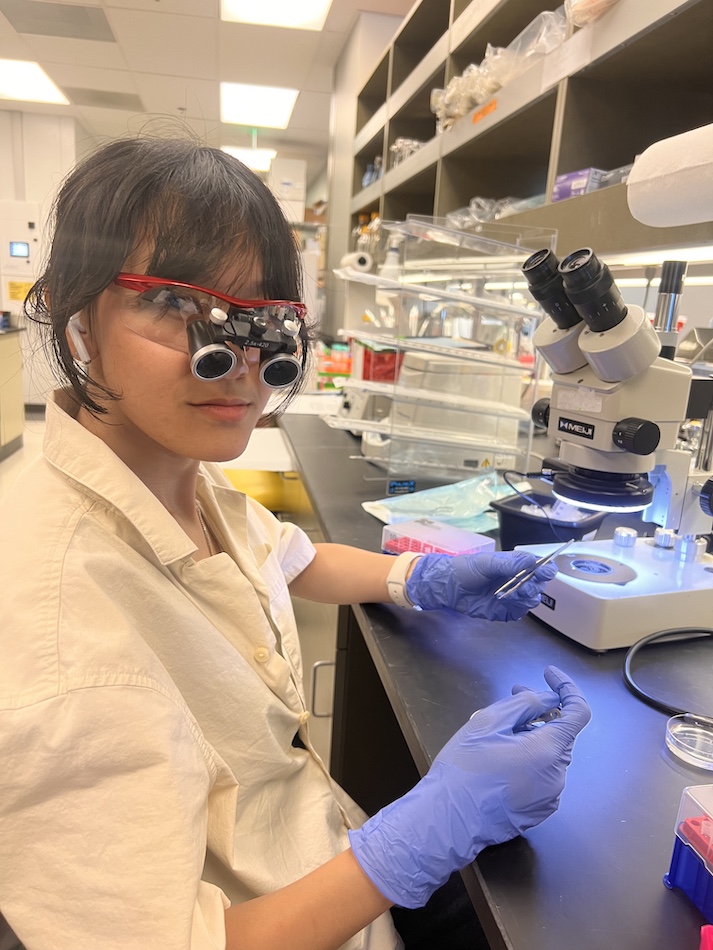

La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI) Postdoctoral Fellow Estefania Quesada-Masachs, M.D., Ph.D., a member of the von Herrath Lab, is investigating cellular communication in the pancreas. She wants to know whether insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas express markers that trigger T cells to mistakenly kill them. Her work brings us closer to understanding the roots of type 1 diabetes.

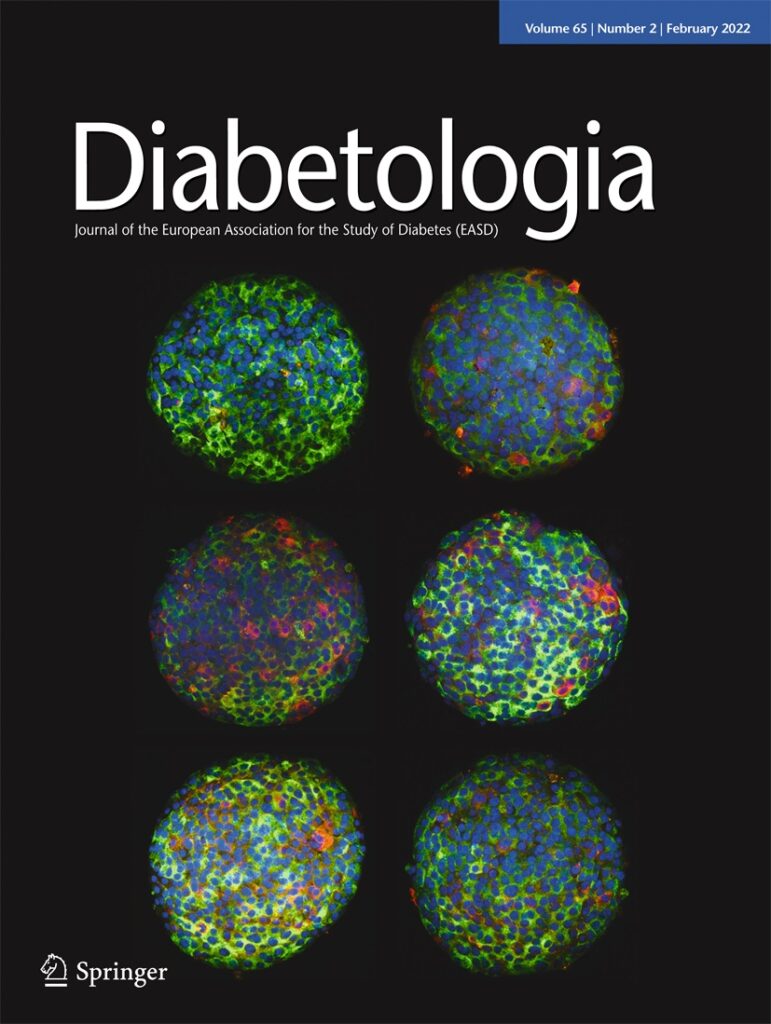

In this Q&A, Quesada-Masachs shares her most recent findings, which were published in the February issue of Diabetologia.

Q: What big question were you trying to answer with this study?

Quesada-Masachs: I wanted to figure out whether beta cells in the pancreas are expressing HLA class II in patients with type 1 diabetes. These beta cells are the ones that die in type 1 diabetes. Figuring out whether these cells express these proteins, is important to understand how they communicate with CD4+ T cells.

We looked at pancreatic tissue section slides from the Network for Pancreatic Organ donors with Diabetes (nPOD), and we analyzed samples from healthy controls and from patients with type 1 diabetes. We found that approximately 28 percent of beta cells in patients with type 1 diabetes have upregulated HLA class II in the pancreas.

Q: So are these HLA class II molecules signaling that a beta cell is in danger?

We don’t know whether expressing HLA class II is detrimental to beta cells or a last cry for help. It could be both. These could just be dysfunctional cells, or they could have a lot of stress around them. They might be trying to regulate the cells around them to say “don’t attack me.”

We don’t really know why the beta cells do it. We know it’s probably not favorable for them in the end because they are still attacked in type 1 diabetes.

Q: Your paper calls this area of diabetes research a “controversy.” Why is that?

HLA class II expression in beta cells was first described in the 1980s. But then in the late 80s and 90s, several groups tried to replicate these findings and were unsuccessful.

So part of the scientific community thought that beta cells were not able to express HLA class II and part of the community thought they were able to express HLA class II in certain conditions. For that reason it was controversial.

It was hard to replicate this research because it is difficult to process pancreas and obtain high-quality tissues. We can do this well nowadays thanks to nPOD. Also, the expression of HLA class II by the beta cells is very heterogeneous even within the pancreas of the same individual. Additionally, the antibodies we could use as tools, our microscopy technology, and image analysis software were not as good in the 90s. So much of the work was manual. We have semi-automated software and much better tools now.

In 2019, when my study was already underway, another research group from University of Massachusetts did transcriptomic analysis to uncover an upregulation of HLA class II molecules and class II antigen presentation pathway components in pancreatic beta cells. This was the only study on the topic after 20 years of silence. Our study here at LJI was ongoing, and we decided to keep working since we were using a very different approach than them.

Having two papers arriving at the same conclusion, in our opinion, closes the debate.

Q: What was different about your study?

A: For this study I did immunofluorescence and two kinds of analyses with the nPOD samples. I did whole tissue analysis using a machine learning approach, and this was the part where my colleagues in the LJI Microscopy Core, Sara McArdle and Zbigniew Mikulski, helped me. And then I worked with Bill Kiosses in the Microscopy Core, who randomly selected thirty islets for us to look at using confocal imaging.

Islets are the areas of the pancreas where insulin-producing beta cells live. I had thousands of islets in the whole tissue samples, and these are precious samples, so I wasn’t satisfied looking at just 30 islets. So Zbigniew and Sara helped me apply innovations to the project so I could finally analyze more than 7,000 islets.

We also used 3D human cultures with human islets—not animal cells or tissue lines—but actual human islets and human islet microtissues. I demonstrated that stimulating even healthy islets with different concentrations of cytokines can lead beta cells to express HLA class II. That’s when these cells receive inflammatory stimuli, because cytokines are inflammatory molecules. We also did RNA studies and found there was an upregulation in the expression of HLA class II RNA-wise in those “inflamed” islets.

So we settled that controversy, and I’m happy the field can move forward.

Q: What are the next steps for you?

The next question is whether the beta cells are using this HLA class II expression to communicate with CD4+ T cells? Are they inducing any sort of change in the T cells?

This is what I’m trying to answer with my recent Tullie and Rickey Families SPARK Award project. I want to give a yes or no answer to whether this communication is happening.

Learn more about the study in Diabetologia.

Read more:

A cold case no longer: What happened when an LJI scientist revisited a diabetes mystery