Karen Barnes knows what it’s like to encounter a silverback gorilla in the misty mountains of Rwanda.

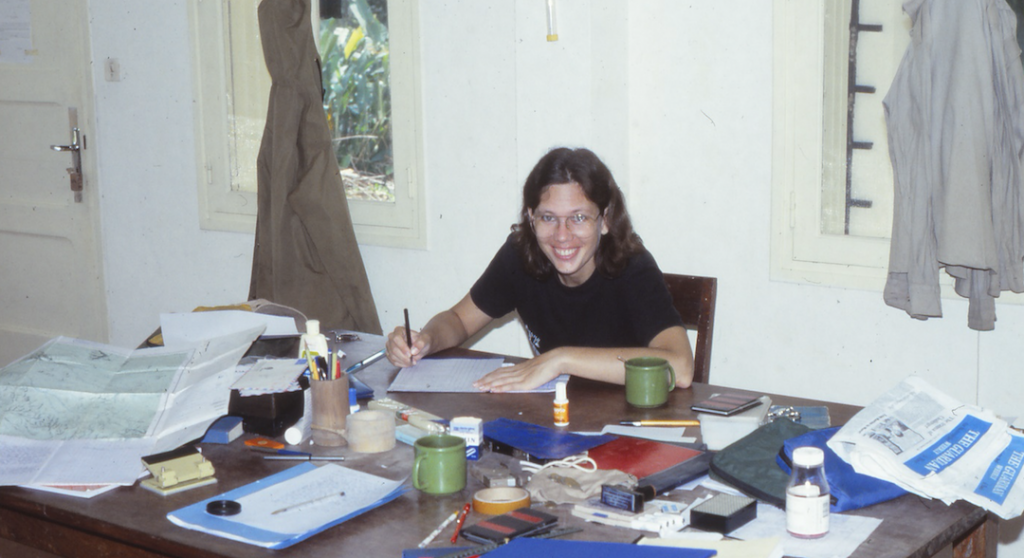

Barnes was in her twenties at the time, tracking mountain gorilla activity at the Karisoke Research Centre, established by primatologist Dian Fossey.

Barnes worked with a team of trackers to map the gorillas’ movements, and she visited a gorilla group each day. This meant following three gorilla troops across a landscape of valleys and dormant volcanoes. “The only rule was to be back in camp by nightfall,” says Barnes.

The goal was to track each individual’s relationship to another and to learn how they used the terrain. Through the work, Barnes saw flashes of gorilla personality. Once, a young gorilla tried to cause havoc by pulling a small tree down on his troop. “He wanted to have a laugh,” Barnes says.

Barnes and the team also kept tabs on a lone silverback, a king among primates.

One day, Barnes was hiking through the forest when she stepped out of the trees to find the silverback staring at her. He took a hard look at her. Then he went back to eating leaves.

“I was then a part of his life,” says Barnes. “That was meaningful to me.”

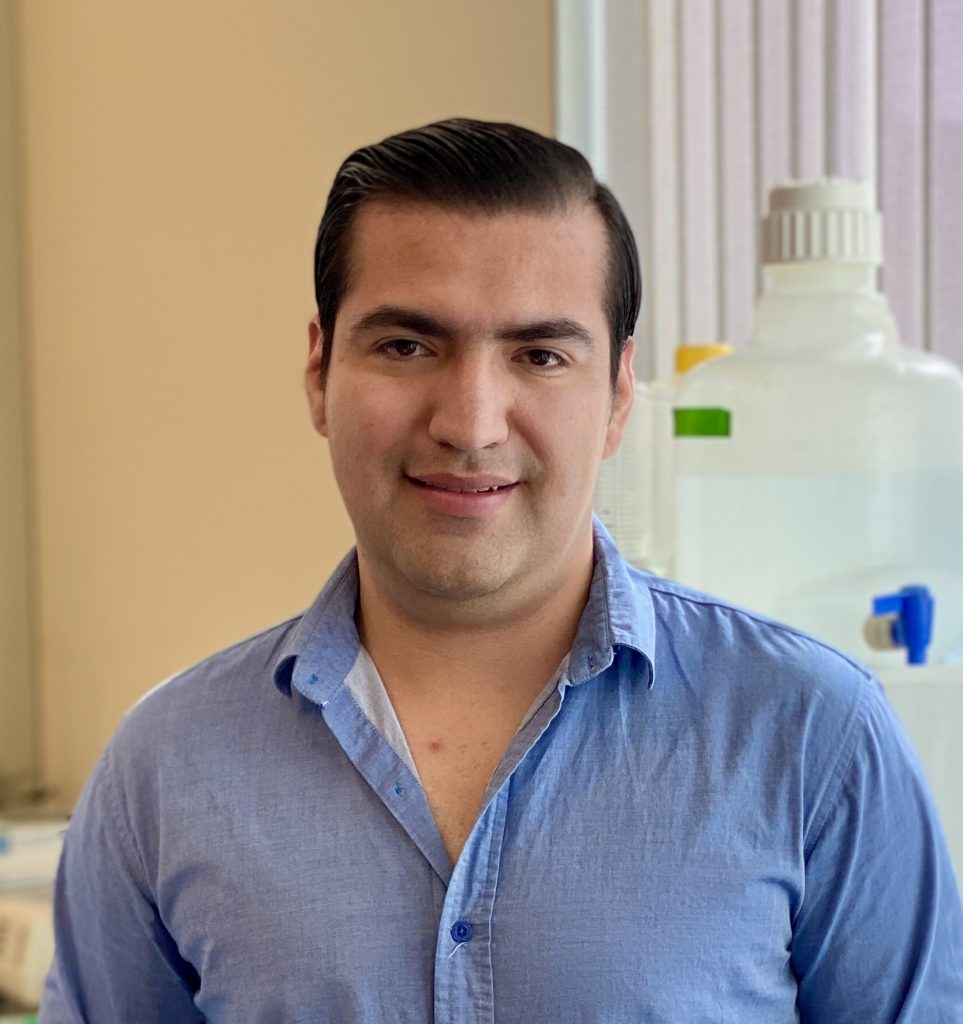

Today, Barnes has stepped back from fieldwork to serve as a Research Administrative Assistant at La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI). Her work helps cutting-edge research run smoothly. “I’ve been very fortunate to have worked in a variety of careers,” says Barnes.

From gorillas to snow leopards—Barnes has seen it all.

Barnes majored in zoology at Cal Poly Pomona. “I only wanted to go through the hassle of grad school if I could do it in Africa,” Barnes says.

She started with a summer course studying spotted hyenas in Africa. The course was meant to give her a taste of fieldwork. Barnes was hooked. She wrote a letter to Dian Fossey, got a position at the Karisoke Research Centre, and hopped on a plane.

“I said farewell to my family—said I’d be gone about a year,” says Barnes.

Some time after working with gorillas (and meeting her husband Richard Barnes, a former student of Jane Goodall, in Rwanda) the Barnes’ were based in Gabon, a country in Central Africa. She tracked elephant herds through the thick forest, studied the defecation decay rates, and worked out the logistics for spending many days in the forest.

“It was wonderful,” says Barnes.

The problem was that forest elephants easily disappear into the trees. Hikers then run the risk of suddenly chancing upon an elephant in the forest and startling it. That doesn’t end well for anyone.

So Barnes rarely saw the elephants she was studying—by design. Instead, the census technique was to walk 20 kilometers into the forest on a compass bearing for four days. Along that straight line, she’d look for elephant dung.

By tracking the distribution of dung piles and the dung decay rate (and factoring in findings from a previous publication as to how many dung piles an elephant produces in a day) the researchers could estimate the number of elephants in the region.

Barnes recorded other signs of animals in the forest. For example, claw marks on a tree meant a leopard had been there. “There were a lot of leopards,” says Barnes.

Once, Barnes was in a spot where the savannah met the forest. In the distance, she saw an animal she couldn’t quite identify. “My first reaction was ‘it’s a bear’ because it was so wide and so tall,” she says. Then she realized it was a leopard, and it was hunting an antelope close to her. This leopard was a good hunter, too. “It was well-rounded because it was so well-fed,” Barnes says.

Eventually, Barnes started looking for a more hands-on career with animals.

“After a couple years of counting rainforest dung piles, there’s a certain sameness to the work,” she says.

After a spending a year in Cambridge, UK, Barnes leapt at the chance to apply for her dream job: keeper at the San Diego Zoo.

Barnes started her zoo career in the Children’s Zoo, where she cared for animals such as Siberian weasels, green-billed toucans and spider monkeys. She also honed her science communication skills as she introduced group after group of children to the basics of zoology. Not long after, Barnes met the head of the zoo’s cheetah breeding facility and was offered a four-month stint working with the cheetahs.

This was the early 1990s. Wild cheetah populations had plummeted for years, and zoos were desperate to breed the cats while managing genetic diversity. The San Diego Zoo was a leader in this area and had established one of the first captive cheetah breeding programs at what is now called the Safari Park.

Barnes ended up working with the cheetahs for fourteen years, and her contributions to the field are highlighted in the zoo guide Husbandry Manual for the Cheetah.

Breeding cheetahs is notoriously tough. Males and females need to be housed separately, and can only be introduced to each other periodically, when the female is at the right place in her estrus cycle. Male cheetahs are shy animals, and they don’t make a move until the female cheetah gives some awfully clear olfactory cues.

On occasions when the match-making worked, Barnes’ next challenge was to separate the couples after they’d finished. Usually the keepers could close a gate to separate the males and females, but the keepers also stayed in the pens in case more cheetah wrangling was needed.

In fact, Barnes went into the cheetah pens every day. Luckily, she found that cheetahs—despite their teeth and claws and speed—are fairly easy to intimidate. She says the cheetahs would often give her a “courtesy hiss” as they waited for their food at the gate. “Mostly, they were anxious to get to their food,” Barnes says.

After years working up in North County (and caring for the Safari Park’s lions, tigers and okapis as well) Barnes was eager for a shorter commute. She moved to a position as a senior keeper on the San Diego Zoo’s “cat string”—the name for the job managing many of the zoo’s cat species, such as leopards, snow leopards, jaguars, lynxes and cougars.

Barnes had a real soft spot for the snow leopards. “They had the most magnificent personalities,” Barnes says. The snow leopards were docile, almost like big house cats. Snow leopards are also very rare, making Barnes one of the few people to ever care for the species.

At the same time, Barnes often served as a zoo spokesperson. She gave tours of the big cat exhibits and often gave interviews to local media for zoo events, such as the birth of a new panda cub.

Barnes worked with the big cats for just over a year when she broke her ankle. At that point, Barnes felt ready to look for jobs outside the world of zoology. She landed at LJI, where she manages the day-to-day needs of four laboratories.

Barnes learned a lot from decades spent working with wildlife. She learned about their life cycles, of course, but she also observed fascinating aspects of animal behavior—both as a species and as individuals.

What holds true across species? “Their unpredictability,” says Barnes. “You can predict what they’ll probably do and you’ll be wrong,” she says.