Fibrosis

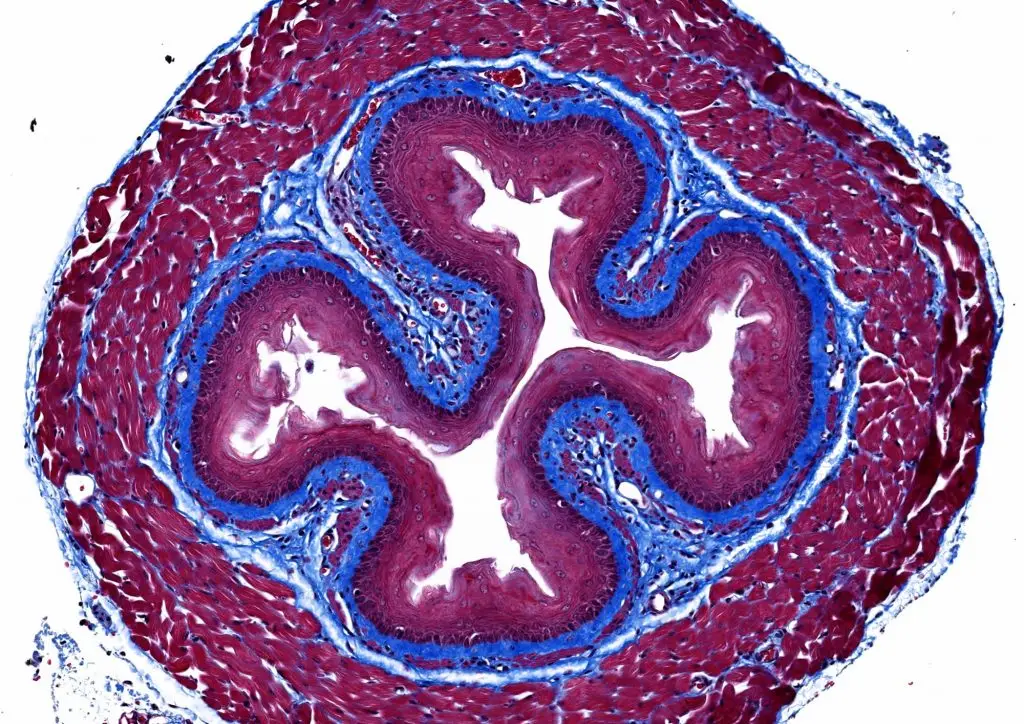

Connective tissues are critical in the body: they lay under the skin and around the organs and blood vessels. Fibrosis occurs when immune cells mistakenly attack these connective tissues, causing the tissues to thicken and scar.

Scarring in the lungs is called pulmonary fibrosis and is associated with other autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and systemic scleroderma. Fibrosis can also be a result of damage from severe asthma or exposure to environmental triggers, such as asbestos, silica and beryllium. Symptoms of pulmonary fibrosis include shortness of breath, persistent coughing, loss of appetite, fatigue, weakness and even clubbing of the fingers.

Our Approach

Researchers at La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI) are working to prevent the scarring in fibrosis from occurring in the first place. LJI Professor Michael Croft, Ph.D., has found a way to counteract airway wall thickening and tissue scarring. In a 2011 study, Dr. Croft found that activity of a pro-inflammatory protein called LIGHT, which is made by T cells, increases fibrosis.

Dr. Croft’s lab then discovered that when mouse models of severe asthma were treated with drugs that block LIGHT, they showed significantly less airway wall thickening and fibrosis. This finding suggests LIGHT inhibitors may be effective in reversing tissue damage in fibrosis, not only in asthmatic lungs, but in other diseases that affect the lung and/or the skin, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, scleroderma and eczema. Drugs targeting LIGHT are now in safety trials and could be used in the future in patients with fibrosis. Dr. Croft’s lab has continued to investigate the role of LIGHT in different types of lung cells.

In a 2020 study, Dr. Croft’s lab uncovered another clue to the origins of fibrosis. They found that a protein called TL1A drives fibrosis in several mouse models, triggering tissue remodeling, and making it harder for lungs and airways to function normally. Their work suggests that TL1A and its receptor on cells could be targets for therapeutics aimed at reducing fibrosis and tissue remodeling in patients with severe lung disease.

Learn more:

Related News

- Research News