LA JOLLA—Your pancreas is studded with cell clusters called islets. In most people, special beta cells live snug in the islets, happily making the insulin that the body uses to regulate blood sugar. But in people with type 1 diabetes, the body’s T cells mistakenly move into the islets and kill the beta cells.

It’s long been thought that having “autoreactive” T cells in the pancreas was a sure sign of type 1 diabetes. Yet a new study led by scientists at La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI) shows that even healthy people have these cells lurking in the pancreas—in surprisingly high numbers.

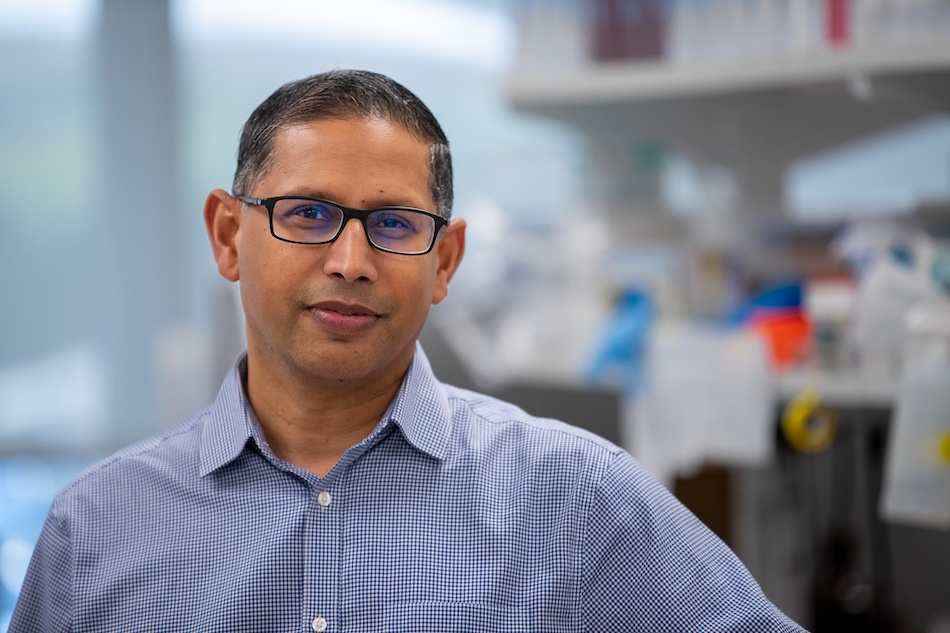

“These T cells are like predators,” says LJI Professor Matthias von Herrath, M.D., senior author of the new study, published October 16, 2020, in Science Advances. “And we always thought that beta cells would die if the predator was there. But it turns out the T cells are already there. They just seem to be waiting for a signal to attack.”

These “predator” cells are called CD8+ T cells, and they specifically target a molecule called preproinsulin, a precursor to insulin. Previous studies have shown that healthy people do have some of these T cells in their bloodstream. No one knew if these cells would travel to the pancreas though—partly because of the challenge of obtaining pancreas samples.

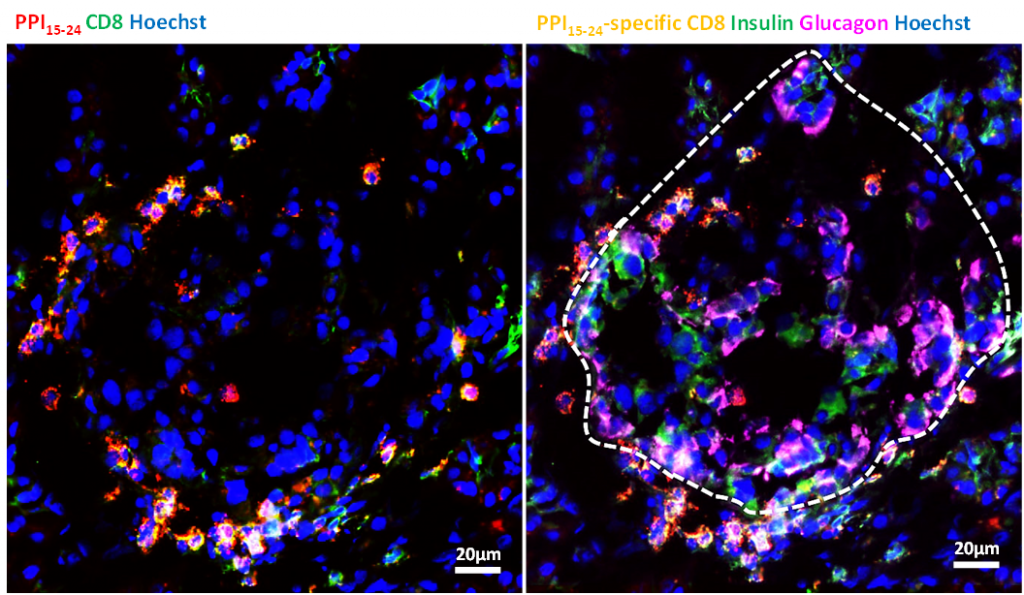

In work spearheaded by Christine Bender, Ph.D., first author of the study and a postdoctoral fellow in the von Herrath Lab, the researchers used a new staining technique to show where these cells gathered in precious human tissue samples. They were surprised to see that even healthy people had proproinsulin-specific T cells swarming in the pancreas.

It appears that high numbers of these T cells in the pancreas are the default—whether you have type 1 diabetes or not. “We were surprised,” says Bender. “Of course, every donor is different, but in general, the numbers are pretty high.”

Of course, people with type 1 diabetes had it worse. Their tissue samples showed the T cells very close to—and even infiltrating—the islets.

“We can’t say that these are the only culprits in type 1 diabetes,” says von Herrath. “But these T cells are the prime suspects.”

These results add evidence for the theory that type 1 diabetes is not caused by malfunctioning T cells attacking beta cells. Instead, the body is already making these T cells and something in the pancreas is triggering the attack. Von Herrath thinks this could mean that an effective type 1 diabetes therapy would need to be local to the pancreas.

Going forward, the researchers plan to take a closer look at how the preproinsulin-specific T cells behave. The team also hopes to investigate other proteins in islets that might attract T cell attacks.

“We still have so many questions,” says Bender.

The study, titled “The healthy exocrine pancreas contains preproinsulin-specific CD8 T cells that attack islets in type 1 diabetes,” was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant R01 AI092453) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Foundation, DFG).

Additional study authors include Teresa Rodriguez-Calvo, Natalie Amirian and Ken T. Coppieters.