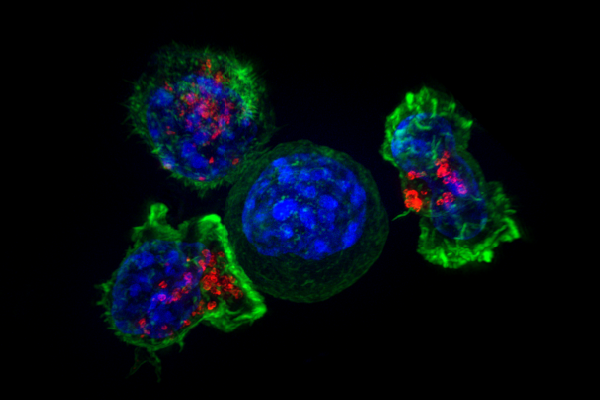

LA JOLLA—Fighting a tumor is a marathon, not a sprint. For cancer-fighting T cells, the race is sometimes just too long, and the T cells quit fighting. Researchers even have a name for this phenomenon: T cell exhaustion.

In a new Nature Immunology study, researchers at La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI) report that T cells can be engineered to clear tumors without succumbing to T cell exhaustion.

“The idea is to give the cells a little bit of armor against the exhaustion program,” says LJI Professor Patrick Hogan, Ph.D. “The cells can go into the tumor to do their job, and then they can stick around as memory cells.”

This research builds on a decades-long collaboration between Hogan and LJI Professor Anjana Rao, Ph.D. Their work has shown the key role of proteins called transcription factors in the cellular pathway that triggers T cell exhaustion.

This work is important because T cell exhaustion continues to plague even the most cutting-edge cancer immunotherapies.

With CAR T therapies, for example, researchers take T cells from a cancer patient and “arm” them by altering the expression of genes that aid in the cancer fight. Researchers make more of these special T cells, which then go back into the patient. CAR T therapies are different from immunotherapies, which aim to activate the patient’s existing T cell population.

With both approaches, T cell exhaustion rears its ugly head. “Many people have tried to use CAR T therapies to kill solid tumors, but it’s been impossible because the T cells become exhausted,” says study co-first author Hyungseok Seo, Ph.D., a former postdoctoral fellow in the Rao Lab who is currently working at Novartis.

The new study addresses this problem by giving T cells the ability to fight exhaustion itself.

To accomplish this, the researchers screened T cells to uncover which transcription factors could boost a T cell’s “effector” program, an important step in readying T cells to kill cancer cells.

This screening process led the researchers to BATF, a transcription factor that they found cooperates with another transcription factor called IRF4 to counter the T cell exhaustion program.

In mouse melanoma and colorectal carcinoma tumor models, altering CAR T cells to also overexpress BATF led to tumor clearance without prompting T cell exhaustion. The CAR T therapy worked against solid tumors.

“BATF and IRF4 are cooperating to make T cells better,” says Seo.

Further testing showed that while IRF4 is important, it shouldn’t be overexpressed to the same degree as BATF. For maximum effect, BATF was overexpressed around 20 times more than in normal cells.

Encouragingly, some altered T cells also stuck around and became memory T cells. This is important because T cell exhaustion often prevents T cells from mounting a strong memory response to recurrent cancers.

“We didn’t just increase the ability of T cells to fight exhaustion—we increased the ability of cells to fight tumors,” says study co-first author Edahí González-Avalos, a graduate student in the Rao Lab who led the bioinformatic analysis for the project.

Hogan thinks overexpressing BATF could be a promising approach for improving CAR T therapies and for tackling some hard-to-treat cancer types, such as pancreatic ductal carcinoma. These types of cancers are known as “immunologically cold” because they don’t spark a strong anti-cancer response from the immune system. T cells don’t fight them in force.

Other laboratories have been exploring ways to make these cold tumors “hot,” so they will attract T cells. The LJI team thinks a promising strategy would combine those approaches with targeting transcription factors to render T cells exhaustion-proof.

“We wouldn’t necessarily need a transgenic approach to do this,” says Hogan. “Maybe even an oral drug molecule could do it, if you knew what transcriptional pathways you wanted to go after.”

The researchers emphasize that BATF is just one of many transcription factors that may prove important to manipulate when countering T cell exhaustion.

“We’re going to keep looking for answers,” adds González-Avalos.

The study, “BATF and IRF4 cooperate to counter exhaustion in tumor-infiltrating CAR T cells,” was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants AI109842, AI040127, DE028227, RR027366, OD018499); a AACR-Genentech Immuno-oncology Research Fellowship 18-40-18-SEO; a Donald J. Gogel Cancer Research Institute Irvington Fellowship; a University of California Institute for Mexico and the United States (UC-MEXUS) and El Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (UCMEXUS/CONACYT) predoctoral fellowship; NIH T32 predoctoral training grant in the UCSD Cardiovascular Bioengineering Training Program; Cancer Research Institute Irvington Fellowship; an Independent Investigator Fund (La Jolla Institute/Kyowa Kirin) and a Career Transition Award from the National Cancer Institute (K22CA241290).

Additional authors of the study include Wade Zhang, Payal Ramchandani, Chao Yang and Chan-Wang J Lio.

DOI: 10.1038/s41590-021-00964-8

###