LA JOLLA, CA—In recent years, immunotherapy, a new form of cancer therapy that rouses the immune system to attack tumor cells, has captivated the public’s imagination. When it works, the results are breathtaking. But more often than not it doesn’t, and scientists still don’t know why.

Publishing in the June 19, 2017, issue of Nature Immunology, researchers at La Jolla Institute for Immunology, identify a subpopulation of T cells in tumors known as tissue-resident memory T cells (TRM) as an important distinguishing factor between cancer patients whose immune system mounts an effective anti-tumor response and those who are unable to do so. Their finding emerged from the first large-scale effort to profile the gene expression patterns of cytotoxic T cells isolated directly from patients’ tumors.

“Systematically studying cancer patients’ immune cells reveals a lot of information,” says LJI Associate Professor and William K. Bowes Jr. Distinguished Professor Pandurangan Vijayanand, M.D., Ph.D., who co-directed the study with Professor Christian Ottensmeier at the University of Southampton, England. “It could be a baseline test to predict whether a patient will respond to immunotherapy and guide the choice of immunotherapy that is most likely to be effective. It is almost like judging tumor immune fitness,” adds Vijayanand. The systematic profiling of tumor-infiltrating T cells will also provide new insight into their basic biology revealing new potential immunotherapy drug targets.

Scientists initially found that when T cells were swarming a patient’s tumor that patient lived longer. Over time, however, they found that T-cells lose their fervor and cancer cells gain the upper hand. In the last decade they discovered why: Inhibitory molecular signals emitted from a tumor or its environment undercut the immune response, making tumor cells invisible to the immune system. One class of cancer immunotherapy drugs, known as checkpoint blockade inhibitors, disables either PD-1 or CTLA-4, two known molecules that allow cancer cells to live and multiply undetected by the immune system.

“The challenge with immunotherapy based on PD-1 and CTLA-4 is that if they work, they work miraculously, but they only work in about 30 percent of patients,” says the study’s first author, Anusha-Preethi Ganesan, M.D., Ph.D., a physician in the Division of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology at Rady’s Children’s Hospital, UC San Diego. “If we are doing all these immunotherapies based on activating T cells to kill tumor cells it is really important to know what the transcriptional profiles of these T cells are, what molecules do they make?”

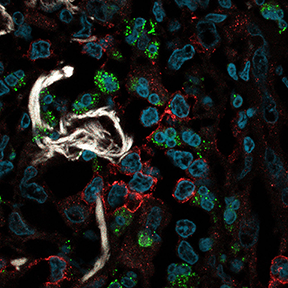

To uncover the underlying reasons why some patients see little or no benefit and to identify those patients most likely to respond, Ganesan utilized advanced genomics tools to define the molecular features of a robust anti-tumor immune response using freshly resected tumors from patients with cancer. Comparing gene expression profiles of cytotoxic T cells (CTLs) isolated from 41 head and neck tumors and 36 untreated, early stage lung tumors with CTLs isolated from adjacent normal lung tissue, Ganesan identified a shared molecular fingerprint between different tumor types suggesting extensive reprogramming of CTLs infiltrating tumor tissue.

Beyond their shared molecular signature, tumor-infiltrating CTLs differed widely in their expression of molecules associated with T cell activation and known immune checkpoints. “There is a huge deal of heterogeneity, which has a lot of implications for immunotherapy,” says Ganesan. “We see the traditional immunotherapy targets but they are not expressed in every single patient, which means not every patient is a candidate for currently available immunotherapies targeted at PD-1 or CTL4-1. That’s why having the full transcriptional profile is so important to understand the entire complexity of the immune network and to identify novel targets.” Interestingly, gene expression patterns that signal the presence of tissue resident memory T cells (TRM) corresponded with better anti-tumor activity.

The only recently identified tissue resident memory T cells act as local first responders that provide rapid onsite immune protection. A large scale analysis in an independent cohort of 689 lung cancer patients confirmed that patients with a high density of TRM cells in tumor tissue survived significantly longer, demonstrating that these cells serve a critical role in protecting against tumor recurrence.

“Any time you remove a tumor, the patient is a ticking time bomb after that. In some people it will come back and it others it won’t,” says Vijayanand. “Our study suggests that the presence of these tissue resident memory cells is an important factor in determining whether somebody is having an effective immune response against cancer and whether they will live longer.”

The work was funded by the William K. Bowes Jr. Foundation, the University of Southampton, Cancer Research UK and the Wessex Clinical Research Network.

Full Citation:

Anusha-Preethi Ganesan, James Clarke, Oliver Wood, Eva M. Garrido-Martin, Serena Chee, Toby Mellows, Daniela Samaniego-Castruita, Divya Singh, Gregory Seumois, Aiman Alzetani, Edwin Woo, Peter S. Friedmann, Emma V. King, Gareth J. Thomas, Tilman Sanchez-Elsner, Pandurangan Vijayanand, Christian H. Ottensmeier. “Tissue-resident memory features are linked to the magnitude of cytotoxic T cell response in human lung cancer”, Nature Immunology, 2017. Doi: 10.1038/ni.3775.

About La Jolla Institute for Immunology

The La Jolla Institute for Immunology is dedicated to understanding the intricacies and power of the immune system so that we may apply that knowledge to promote human health and prevent a wide range of diseases. Since its founding in 1988 as an independent, nonprofit research organization, the Institute has made numerous advances leading toward its goal: life without disease.