LA JOLLA, CA—Seventeen years ago, another viral outbreak was in the news. People wore masks, many were nervous to fly. This outbreak, known as SARS, was caused by a type of coronavirus we now call SARS-CoV-1. The difference was that SARS-CoV-1 was controlled and the virus is all but extinct. The newspaper headlines became a distant memory.

But research on coronaviruses continued in labs around the world, and those studies have helped inform the fast-paced COVID-19 research today.

“We need solutions right now,” says Sara Landeras-Bueno, Ph.D., a postdoctoral researcher at La Jolla Institute (LJI). “But it’s so challenging to stay up-to-date on all the publications.”

Indeed, researchers today are publishing 50 to 100 studies a day on COVID-19, and not all the studies have been subject to rigorous peer review. To help researchers understand the mountain of new coronavirus data, Ying-Ting Wang, Ph.D., Sara Landeras-Bueno Ph.D., Jose Angel Regla-Nava, Ph.D., and colleagues recently led a review comparing findings from more than 200 COVID-19 studies with immunological and virological findings in previous SARS research. Their summary, published this week in the online edition of Trends in Microbiology, emphasizes the need for better animal models and structural studies for COVID-19 treatment and vaccine development.

Regla-Nava, who has experience studying SARS and MERS, explains that the viruses that cause SARS and COVID-19 are 79 percent identical. This means we could potentially learn a lot from SARS about how long immunity might last against the novel coronavirus, called SARS-CoV-2. Several recent studies have shown that a person exposed to SARS can still have SARS-fighting antibodies for many years after infection. But the actual number of antibodies really declines after two years.

This could mean that vaccines and natural immunity against SARS-CoV-2 may only provide protection for a few years.

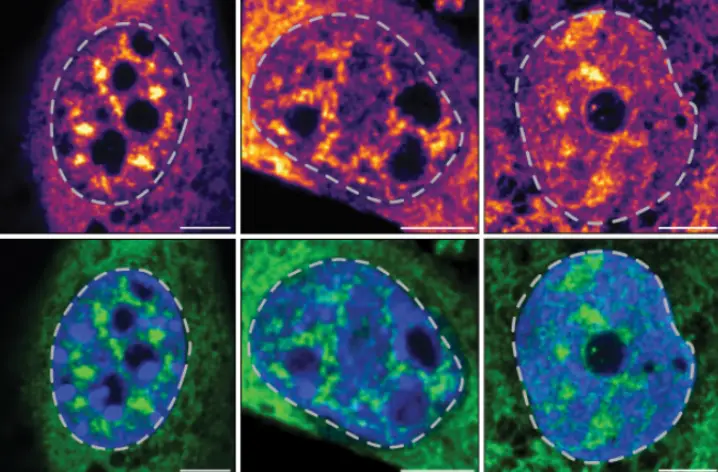

The researchers also looked at structural studies showing where antibodies can attack these viruses. Both viruses have “spike” proteins that protrude from the virus and are exposed to the human immune system.

Can SARS antibodies also attack these spike proteins on the novel coronavirus? “Although most of the proteins in these viruses are similar, they are not exactly the same,” says Landeras-Bueno. “So it was not easy to find antibodies that could neutralize both.”

Regla-Nava believes we’ll have to tweak current mouse models in the effort to develop vaccines that can elicit truly neutralizing antibodies. “It’s really important to have good animal models for these studies,” he says.

In the meantime, the LJI team is hard at work as part of the LJI Coronavirus Task Force. Wang says it remains critical to try to stay up-to-date with breakthroughs worldwide and summarize those findings in a useful way.

“This is what we can do for now to help the scientific community,” says Wang.

This review was supported by the Ley, Shresta and Saphire labs at LJI. The work was funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation grant # INV-006133.

Full citation:

Ying-Ting Wang, Sara Landeras-Bueno, Li-En Hsieh, Yutaka Terada, Kenneth Kim, Klaus Ley, Sujan Shresta, Erica Ollmann Saphire and Jose Angel Regla-Nava. Spiking Pandemic Potential: Structural and Immunological aspects of SARS-CoV-2. Trends in Microbiology, 2020.

Doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2020.05.012

Read the review: Spiking Pandemic Potential: Structural and Immunological aspects of SARS-CoV-2