Atopic Dermatitis / Eczema

Atopic dermatitis is the most common type of eczema. It occurs when a person’s immune system causes inflammation of the skin, which also makes the skin more vulnerable to environmental irritants and allergens. Patients with atopic dermatitis often experience red, itchy skin, red and brown blotches on the skin, and raw, swollen patches on the skin. The condition can be very painful and can lead to complications like skin infections.

Atopic dermatitis affects 15 to 20 percent of children and 1 to 3 percent of adults. Although there is no cure for atopic dermatitis, the symptoms can be treated with topical medications, phototherapy, immunosuppressant drugs, biologic drugs, and steroids.

The exact cause of atopic dermatitis is unknown. The condition can run in families, which suggests there is a genetic component. In some people, a mutation in the gene that encodes the Filaggrin protein contributes to the disease.

Our Approach

LJI scientists are working to help patients with atopic dermatitis/eczema by uncovering the molecular drivers of inflammation.

LJI Professor Michael Croft, Ph.D., is investigating how proteins related to tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and other “costimulatory molecules” contribute to atopic dermatitis. Dr. Croft discovered many activities of OX40, a costimulatory molecule that promotes division and cytokine production in T cells.

Dr. Croft’s research has led to encouraging clinical studies. In 2023, Japanese pharmaceutical company Kyowa Kirin Co., Ltd., shared findings from a Phase 2b trial focused on the efficacy and safety of an experimental monoclonal antibody treatment targeting OX40. This experimental treatment, called rocatinlimab (KHK4083/AMG 451), was studied in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (not adequately controlled with topical agents). As the researchers reported, rocatinlimab showed the potential to yield long-lasting improvements for adult patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Phase III studies to evaluate long-term efficacy and safety are currently underway.

Investigating flare ups

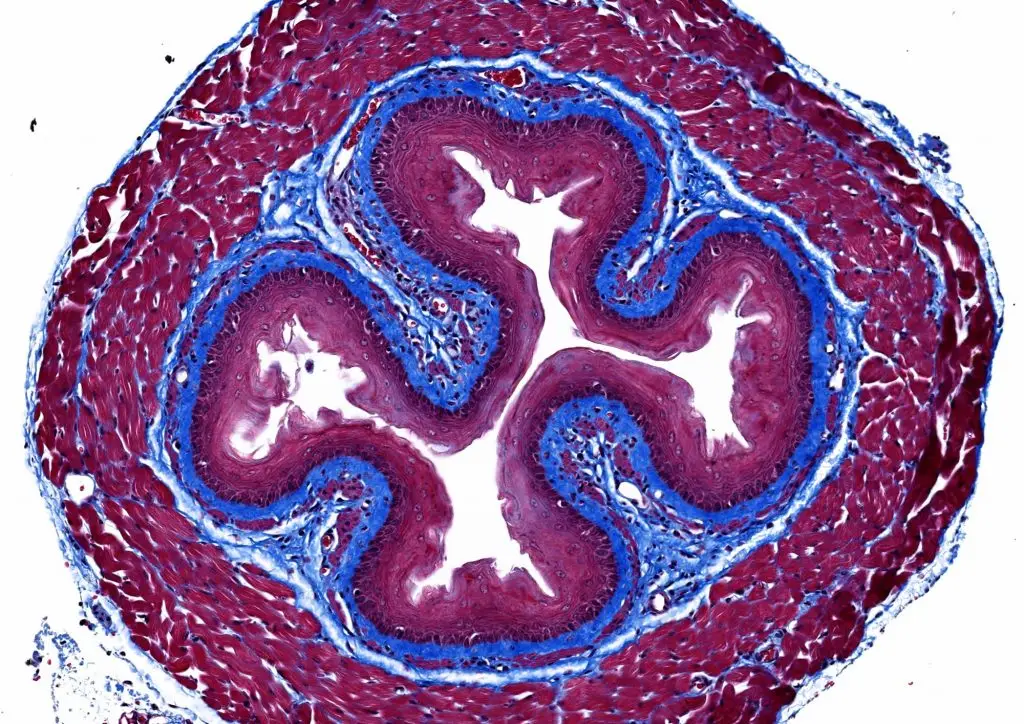

In his career at LJI Professor Emeritus Toshiaki Kawakami, M.D., PhD., developed animal models of atopic dermatitis to study how immune cell signaling can make flare ups better or worse. His follow-up studies of human skin tissues, confirmed that these mouse models mimic the allergic immune response seen in humans. One of Dr. Kawakami’s critical discoveries was that a protein that controls gene expression, called STAT5, drives up the number of immune cells called mast cells in the skin of some atopic dermatitis sufferers. His lab also reported that a different signaling factor called phospholipase C-beta3 (PLC-β3) blocks STAT5. These discoveries suggested that atopic dermatitis severity could be modulated either by muffling STAT5 or boosting PLC-β3 activity. Dr. Kawakami went on to establish mouse models for eczema vaccinatum and eczema herpeticum, serious skin infections caused by vaccinia and herpes simplex viruses, respectively, in patients with eczema.

The roles of LIGHT and TWEAK

In collaborations with Dr. Kawakami, Dr. Croft’s lab also published research showing that LIGHT, another member of TNF family of proteins, directly controls the hyperproliferation of skin cells called keratinocytes as well as the expression of inflammatory proteins made by keratinocytes that contribute to the clinical features of atopic dermatitis. The researchers found that a therapeutic antibody that neutralizes LIGHT activity successfully suppresses disease symptoms, suggesting that therapies based on blocking LIGHT may additionally help patients suffering from atopic dermatitis.

Dr. Croft has also reported that another protein called TWEAK, which is again related to TNF, plays a role in the process to recruit immune cells into the skin. This work suggests TWEAK could be a further potential therapeutic target for the treatment of inflammatory skin diseases such as atopic dermatitis and even psoriasis.

Learn more:

Related News

- Institute News

- Research News

Research Projects

As our knowledge of the FceRI-mediated signal transduction has grown for the last two decades, the need to study in vivo roles of this pathway in disease settings encouraged the [...]